Maximising Thinking Capacity (Learning) In Your Classroom

Sep 10, 2024

Working Memory is the biggest predictor of children’s achievement we have. In essence, it is our 'thinking capacity' and is that important for learning that is has been likened to the 'new IQ' by some researchers.

Working Memory is our capacity to think about and process information; both new (e.g. what’s being taught) and old (i.e. memories of previous learning). It provides children with the ability to follow classroom instructions, grasp the concepts we’re trying to explain, to plan what the next step on an activity may be, to draw connections between different parts of their learning, and to process lots of information (e.g. in phonics and mental maths). If you want the children in your class to ‘think’ about something, however big or small, you’re asking them to use their Working Memory capacity to do this.

Working Memory therefore underpins every aspect of learning, and is the reason why it can predict academic performance in standardised tests like SATs and GCSEs so well. You will already intuitively know this (whether you had the word for ‘Working Memory’ in your vocabulary), as it’s the reason why we set about teaching a Year 1 class differently to a Year 6 class (SATS pressures aside). Younger children often need more visual aids and explicit modelling, chunked instructions, and more frequent repetition, while we expect older children to handle a faster pace and more verbally complex instructions.

Do We Always Maximise Our Working Memory Capacity In Learning?

While children can have different Working Memory capacities, there are a lot of factors which can impact the extent that this capacity can be fully maximised at any point in time. The main reason for this is because it’s attentionally hard and tiring to maximise our Working Memory capacity; at any time, there’s always a variation in how much attentional capacity we might have dependent on a range of internal and external factors. As a simple example, we instinctively know that we could achieve more planning/marking in a quiet staff room than taking our laptop into the middle of a noisy playground.

Let’s look at these factors to help us to identify what barriers there may be to children being able to maximise their Working Memory capacity in our classroom:

Sustained Attention

Sustained attention is our ability to focus on a task for an extended period. Sometimes we see that children can work well and achieve a lot when they first get started, but that they become tired and struggle to concentrate quickly. When this happens, they have less capacity to use their Working Memory, process information, think and learn, and tasks feel like they’ve become an uphill struggle to achieve. The more sustained attention a child has, the better they are at utilising their Working Memory for longer periods of time (Diamond, 2013).

Distractibility

Working Memory is about processing information in mind. When distracted, by definition, new and irrelevant information gets into our mind which takes up some of this capacity and makes the task at hand much more challenging. When thinking of distractions, we typically think about external ones such as noise, movement, or visual stimuli which pulls a child's focus away from the task at hand. Even brief distractions can cause "memory leaks," where information held in Working Memory is lost, requiring the child to start a task over again from the beginning (Cowan, 2017). For instance, we often see that some children become increasingly frustrated with background chatter in class because they know they can complete the questions, but that these distractions are stopping them from being able to fully process the information (i.e. use their Working Memory capacity) to achieve the answer. They keep starting, stopping, restarting, stopping; it’s irritating and something a lot of us too have experienced when we’re trying to concentrate on something and get interrupted.

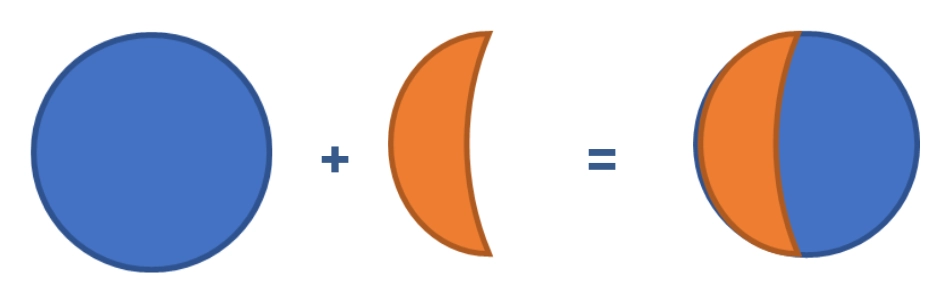

Working Memory capacity being taken up by distractions (e.g. noise, anxiety in orange), leaving less available for learning

Emotional Factors

Related to the above, distractions can also come internally. Any heightened emotion, whether it be anxiety, anger or excitement makes it much harder for us to keep focused because we’re distracted by our internal thoughts and want to do something else. These heightened emotions consume and take up Working Memory capacity, leaving less resources to think about the task at hand (Eysenck, Derakshan, Santos, & Calvo, 2007). A child who is upset or angry may struggle with tasks that they would typically find manageable. Emotional upheaval can cloud the "mental workspace," making it difficult to hold and manipulate information (Blair & Ursache, 2011).

We also see this in task specific occasions where, for instance, a child who experiences maths anxiety is too distracted to be able to think and process the numbers in front of them despite having Working Memory capacity to do so. These emotional pulls on attention is also a key factor in exam success, and the reason why performance within exams is typically less than within the normal classroom environment.

Sleep and Fatigue

We’ve all experienced a lack of sleep at some times, and know how much harder it is to think, plan and engage in mentally taxing conversations. A child who is tired, either from a lack of sleep or other reasons, will have much less ability to use their Working Memory capacity on that day, leading to reduced learning and achievement (Lim, Dinges, & Chee, 2010). This is why, when a child is struggling to make progress, asking their parents about sleep quantity and quality, as well as considering frequent rest breaks to replenish their attentional capacity can be very helpful.

Quick Anecdote: Kainan and Aliyah

Kainan and Aliyah are both Year 4 students but with different attentional and emotional profiles. Kainan struggles with distractibility and often finds their mind wandering during lessons, affecting their ability to maximise their Working Memory capacity when thinking about tasks. Aliyah, on the other hand, experiences anxiety, particularly during tests, which acts as an internal distraction. Their teacher placed Kainan closer to the front of the class, away from windows and other distractions, while incorporated mindfulness sessions to help Aliyah help manage anxiety levels. For both, this reduced their attention being distracted by other things, and meant that they could think and process much more information (i.e. maximise their Working Memory capacities) and learn at a greater pace in class.

Cognitive Load and Working Memory

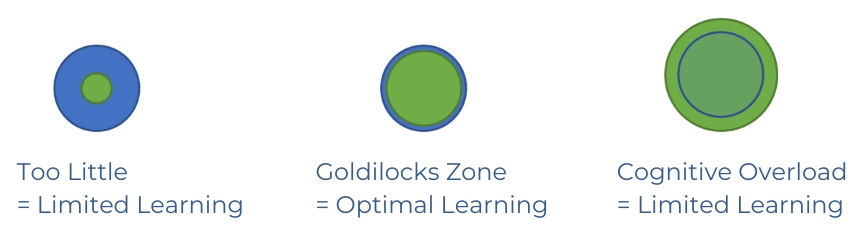

Another way in which Working Memory is sometimes talked about is with reference to the ‘Cognitive Load’. The key idea here is that we’re always trying to match our teaching load with a child’s thinking capacity / Working Memory capacity. If we present too little information, they’re learning at a slow pace. If we present too much information, they can become overloaded and overwhelmed which leads to little learning. However, finding that ideal spot (Goldilocks Zone) where the teaching load matches a child’s thinking capacity / Working Memory capacity sees them be able to maximise their learning, and their rate of progression is optimal.

Blue = Child’s thinking capacity / Working Memory capacity

Green = Teaching Load

The balancing act

Another way to think about Cognitive Load is to imagine a set of scales. On one side, you have the Teaching Load, which includes all the information and tasks that need to be processed. On the other side, you have Working Memory capacity of the child, which is the ability to hold and manipulate this information. When the scales tip too far in either direction, learning becomes minimal, and is why it feels like teaching is always an evolving balancing act.

The cliff edge

One caveat to the above analogy is that, in many ways, it’s more like a cliff edge. We can increase the rate of learning by increasing the Teaching Load only up to the child’s Working Memory Capacity. Past this point, Cognitive Overload happens and there’s a sharp drop in their rate of learning. That is, Cognitive Overload occurs when the Teaching Load placed on a child’s Working Memory exceeds it’s capacity. In simpler terms, it's like trying to pour a bucket of water into a small cup; the cup can’t handle it and the water quickly starts to spill out everywhere. When this happens, children may become visibly stressed, disengaged, or start making frequent errors. They might also miss out on new information because they are still struggling to process the previous content.

Cognitive Overload isn't just an academic concern; it has emotional and psychological implications as well. Frequently overloaded children can experience increased stress and reduced self-esteem, which in turn can impact their overall well-being and attitude towards learning (Plass, Moreno, & Brünken, 2010).

In search of the Goldilocks zone

The hard thing for us when trying to find the Goldilocks Zone is that children’s thinking capacity changes dependent on the day (e.g. sleep, excitement for an event, emotional because of a playground upset), and the environment in that moment (another class are having PE right outside your window). This is why we sometimes question ourselves why a lesson which we thought would go really well, didn’t. It’s also why we intuitively adapt the Teaching Load around times such as Christmas or the last weeks before Summer when excitement is high.

Metacognitive Self Awareness and Achievement

When talking about Cognitive Load above, the emphasis here is on how we can match the Teaching Load to the child’s Working Memory capacity. However, children are not passive recipients of learning. On the one hand, there is often a desire to feel challenged and stretch themselves and their capacity. On the other, there is a fear and aversion to being overloaded; knowing that this will lead to failure.

Avoiding the cliff edge

Children and adults are not always self-aware of their capacity (a part of metacognition). What we see is that most prefer to stay well within their ‘safe zone’ of learning rather than potentially fall over the cliff edge and experiencing the negative emotions that come with being overloaded. Especially for children who may have experienced frequent overload in the past, they stay well clear from their limits and are the ones who frequently say “I can’t do it” and want a task to be broken down or scaffolded before they’ve even started to think about it.

Self-awareness = Maximising capacity

When children have a clearer awareness, understanding and confidence in their own thinking capacity, this allows them to actively control their cognitive resources and know how far they can really stretch themselves. We also see that children with even moderate problem-solving abilities start to find their own strategies to break tasks down into something which is personally manageable. This self-regulatory approach not only sees children more frequently maximise their Working Memory capacity, but also prevents them from experiencing cognitive overload due to knowing when and where to ask for help. As a result, it’s easy to understand why the research shows that such self-awareness in their own abilities improves achievement outcomes for children.

8 Reflections To Increase Rate Of Learning In Your Class

While there are programmes we can use to increase children’s ‘raw’ Working Memory capacity, there’s also a lot which impacts our class being able to always maximise this capacity. With your class being unique, the best, most practical and impactful approaches will come from your reflections. If there’s the opportunity, the following questions are often found to be helpful for teachers to identify what could support your class the most:

- Understanding and Assessing Working Memory:

• How do you currently identify which students might be struggling with working memory demands during lessons? - Strategies for Maximizing Working Memory:

• Can you share an instance where changing the classroom environment (e.g. adjustments for external distractions) significantly improved a student's ability to focus and process information? - Handling Cognitive Load:

• What strategies do you employ to find the 'Goldilocks Zone' of cognitive load for your students? - Supporting Sustained Attention:

• How do you alter lesson plans when you notice attention spans waning? - Addressing Emotional Factors:

• How do you support students who may be experiencing emotional distress or anxiety that affects their cognitive processing? - Impact of Physical Factors:

• How do you assess and address the impact of sleep and fatigue on student performance? - Promoting Metacognitive Skills:

• How do you encourage students to become more self-aware of their thinking capacities and limits? - Adapting Teaching Load:

• How do you balance the need to challenge students with the risk of cognitive overload?

Want To Support Children Improve Their Working Memory In Your Classroom? MeeMo provides a practical, flexible, and engaging 10 minute whole-class training to help every child maximise their individual thinking capacity.

Stay connected with news and updates!

Sign up to receive updates, resources, inspiring blogs and early access to our courses.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.